|

Recent State and Local Education News

|

VDOE is stepping in after several parents expressed concerns about the special education program.

In addition, according to a complaint that’s been filed by the ACLU and Legal Aid Justice Center, they looked at information from the 2014-2015 school year and found African American students were issued 98 percent of the long-term suspensions.

School reform: What went wrong, what went right, and what we should do in the future

Washington Post

September 19, 2016

For years the United States has embarked on an effort to reform its public education system, a civic institution, that has been based on market principles and the belief that standardized testing is the best way to assess students, teachers, principals, schools, districts and states. The results? Not exactly what market reformers had hoped.

A new book edited by William J. Mathis and Tina M. Trujillo takes a look at, as they write in the post below, “what went wrong, what went right, and what we should do in the future.” The book is titled “Learning from the Federal Market-Based Reforms: Lessons for the Every Student Succeeds Act,” and was published by the National Education Policy Center, a think tank at the University of Colorado at Boulder. Mathis and Trujillo asked a number of scholars to assess key aspects of the reform agenda and they assembled the work in a smart, wide-ranging book.

Staples column: Virginia's education commitment to military children

Richmond Times Dispatch

September 15, 2016

No group of parents pays closer attention to comparisons of state public school systems than the men and women who serve in our armed forces. I know this from personal experience, having served as a principal just off post from Fort Lee; as the superintendent of a school division bordering Camp Perry, the Yorktown Naval Weapons Station and Langley Air Force Base on the Peninsula; and now as Virginia’s chief school officer.

My experience also has convinced me that the commonwealth has a special obligation to the estimated 72,000 military-connected children enrolled in its public schools. This responsibility includes military-friendly rules for enrollment and the transfer of credits and high expectations for learning and achievement.

Earlier this year, a study was published by Achieve — a national education reform group — comparing proficiency rates on the battery of tests known as the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) with achievement on state tests, including Virginia’s Standards of Learning assessments. I was not surprised that this study caught the attention of military parents.

|

Recent National Education News

|

New catalyst for bilingual education on November ballot

The Sacramento Bee

Spetember 19, 2016

Bilingual teacher Liliana Martinez does not speak a word of English to her 27 kindergartners at the Thomas Edison Language Institute in Sacramento.

She speaks Spanish. All the time. Even during recess.

Eighteen years ago, over the span of a generation of schoolkids, California voters agreed to eliminate most public school instruction in languages other than English through Proposition 227. Since then, the desire by English-speaking families to immerse their children in foreign language instruction has grown, along with a push to revoke limits on non-English education.

In November, California voters will have a chance to reverse parts of the 1998 law, possibly enabling an expansion of bilingual schools and classes. Proposition 58 would eliminate the need for waivers and allow districts to create new language programs in consultation with parents on behalf of 1.4 million English learners.

Putting Education At The Center Of The 2016 Presidential Campaign

Huffington Post

August 19, 2016

Last week over two hundred students, faculty, and community residents jammed into the Hofstra library auditorium for a Debate 2016 panel on the future of education in the United States. Life-sized Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump puppets sat by the podium, observing, and hopefully preparing to report back to the candidates.

Panelists included Carol Burris, Executive Director of the Network for Public Education, Max Eden, Senior Fellow, Manhattan Institute, historian Yohuru Williams from Fairfield University, Leo Casey, Executive Director of the Albert Shanker Institute, Kevin Welner, a Colorado University (Boulder) Professor and Director of the National Education Policy Center, John Hildebrand, Newsday Senior Education Writer, and Hofstra professors Alan Singer (aka Reeces Pieces), Andrea Libresco, and Elfreda Blue.

Carol Burris, a former high school principal and a spokesperson for the national opt-out of high stakes testing campaign opened. She sees the current call for “school choice” as the biggest threat to public education in the United States. “Choice” has become a euphemism for charters and vouchers and the privatization of education in the United States. But according to Burris privatization will not work for education. “When a local pizza place closes, it is not such a big deal. But when a charter school fails and closes, hundreds of children are displaced.”

|

|

|

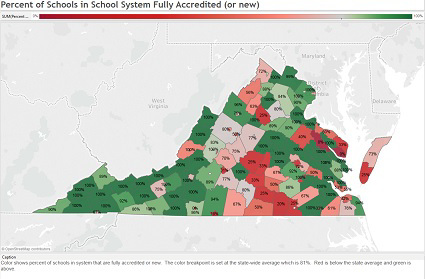

Where are schools that did not receive full accreditation in 2016?

The big news in education this week was the annual release by the Virginia Department of Education (VDOE) of accreditation results for schools across the Commonwealth. As the

press release from VDOE noted, 81% of schools were fully accredited this year, up from 78% last year.

Regular readers of Compass Point may remember our visual analysis of the results from 2015 and so again this year we wanted to look at several aspects including:

- which school systems had all their schools fully accredited

- where schools are that did not receive full accreditation

- whether those schools are highly concentrated in certain school systems or evenly spread out

- and what that same question of concentration yields when our focus narrows to those schools denied accreditation.

The set of four visuals can be accessed

via this link or by clicking on any of the graphics below.

First we look at the percentage of schools in each school system that were fully accredited (or so new that they do not yet have enough of a track record to be rated for accreditation). As the VDOE noted, 53 school systems had 100% of their individual schools receive full accreditation, up from 36 last year. (Certainly worth celebrating.) Of course in the map below, those are the dark green school systems. Those in lighter shades of green did not have 100% of schools fully accredited but were above the state average of 81%. Those in shades of red fell below that 81% average state mark.

|

|

The take aways from this map are that school systems with at least one school receiving a warning or denial are spread across the state, though in general, a lot of western Virginia counties had 100% full accreditation rates. School systems with very low rates are generally concentrated in South Central Virginia, larger urban areas and along the Chesapeake Bay.

Next we take a look at where the largest numbers of warned or denied schools are located. Keep in mind that in a small 3 school district (one elementary, one middle and one high school), having just one school receive a warning would result in a system-wide rate below the state-wide average of 81%. As can be seen below, a fairly large number of schools that were warned or denied accreditation fall in the larger urban areas.

The third graphic makes this even more clear. Close to 20% of all schools that were warned or denied are in four school systems - Richmond City, Norfolk, Henrico and Newport News.

This concentration of schools of concern is even more pronounced once we focus in on those schools with consistently low pass rates on SOLs year after year - the subset that is denied accreditation rather than just being warned. In the graphic below, it's apparent that two thirds of the individual schools denied accreditation are in only three school systems - Newport News, Richmond City and Norfolk.

Not surprisingly, these systems are also among those with high overall poverty rates, as was noted in

recent news analysis of poverty rates in the Commonwealth. This may mean that a search for causes of failure to meet accreditation standards should look at systemic issues as well as the actions taken within any individual school.

We mention this because, in any debate about the success of schools, the key role of teachers is always central to the conversation. Over several decades, one of the proposed solutions to improving schools is to make it easier to dismiss teachers who are deemed ineffective. However this means dismantling the system of teacher tenure or continuing contracts which establish a clear set of procedures that must be followed in dismissing a teacher for cause. The debate over modifying or eliminating teacher tenure is often heated and a recent California legal case asking the state courts to declare such a system unconstitutional received significant attention and news coverage.

This week CEPI's Senior Fellow, Dr. Richard Vacca, published the first issue of our Education Law Newsletter and reviews Vergara, the California case, in detail as well as offering a list of policy implications. We excerpt portions of that Education Law newsletter

below.

Finally, in

this week's poll snapshot we look back at several years when we asked the public here in Virginia whether they supported teacher tenure.

We hope you find this collection of analysis and insights useful.

Sincerely,

CEPI

|

Poll Snapshot - Support for teacher tenure

Job tenure is a concept unique to the educational sector and has long been a topic of discussion and debate in education policy circles. But what does the public think about teacher tenure?

From 2010-2011 to 2012-13 we asked just that question in our Commonwealth Education Poll. After a shift toward opposition to tenure in 2011-12, Virginians were again more divided on the issue in the 2012-13 year. A plurality of respondents, 48%, opposes offering tenure, while 38% support it and 14% are undecided.

School employees and retirees are more likely than other state residents to favor tenure, with 50% supporting. Partisan differences exist as well with 43% of Democrats favoring tenure, while only 37% of Independents and 34% of Republicans do.

To read the full 2012-13 poll, visit our

website. |

Education Law Newsletter - Teacher Tenure Challenged: The California Case

Excerpted from the September edition of CEPI's Education Law Newsletter. This issue is written by Dr. Richard Vacca and looks at Vergara, et al. v. State of California, et al. (2016). Read the full newsletter on our

website.

Overview

Teacher tenure remains a source of controversy both in the popular media and professional literature. Past commentaries in this series have been devoted to issues of local school system tenure policy and practice. In state legislatures and in local school board meetings teacher tenure is a hot topic of discussion. In communities across this country, especially as student statewide academic test scores and accreditation ratings for individual schools (elementary, middle, and secondary) are published in local newspapers, parent groups and tax payer organizations are demanding that incompetent (poorly performing, ineffective) teachers be quickly identified and summarily removed from public school classrooms. In their view removing “poorly performing and ineffective teachers” from classrooms will improve instruction and boost student learning—especially in lower performing schools.

Tenure Status. As my late coauthor Bill Bosher and I observed, public school teachers have relied on achieving tenure as a means of job security. With historical roots in property law, the intent of tenure is not to guarantee permanent employment. Once a successful probationary period is served and tenure is achieved, a teacher is protected from unlawful, arbitrary, and capricious board actions and the employing board must follow orderly procedures (enumerated in state statute) if and when cause for dismissal is established. (Vacca and Bosher, 2012) As Russo reminds us, “[i}n tenure or continuing contract arrangements, since employees have acquired substantive due process rights, they are entitled to procedural safeguards before they can be dismissed from employment.” (Russo, 2004) In states where collective bargaining agreements exist, the need to establish cause for dismissal and to follow mandated procedural requirements further strengthen teacher tenure guarantees.

********

Vergara, et al. v. State of California, et al. (2016)

Facts. Plaintiffs filed suit in Superior Court, Los Angeles County, against the State of California and several state officials seeking a court order declaring five sections of the California Education Code unconstitutional. The challenged provisions covered K-12 public school teacher tenure, dismissal, and the role of seniority in laying off teachers. In essence plaintiff students claimed, among other things, that the named statutes created an oversupply of “grossly ineffective” teachers inevitably having a negative effect on minority students “right to education.” Minority students, they said, were being provided with an education that was not basically equivalent to that being provided to more affluent and/or white peers. The Superior Court judge ruled in their favor. Defendants appealed the ruling.

********

Appellate Court Discussion and Rationale

Citing California case law on point, the appellate court established that the extent of its de novo review requires an analysis of factual determination based on evidence presented at trial. The trial court’s findings of fact are reviewed for substantive evidence. Moreover, “as with any legislative act, statutes related to education are provided a presumption of constitutionality. Any doubts are resolved in favor of a finding of validity.” And, said the Court, “[p]olicy judgments underlying are left to the Legislature; the judiciary does not pass judgment on the wisdom of legislation. Courts do not sit as super-legislatures to determine the wisdom, desirability, or propriety of statutes.” Following a discussion of equal protection, class actions, and the difference between rational basis and strict scrutiny reviews, the appellate court narrowed the scope of the review by establishing that it would determine whether plaintiffs had demonstrated that the challenged statutes cause a certain class of students to suffer an equal protection violation.

Regarding Group 1, described by plaintiffs as an “unlucky subset” of the general student population that is denied the fundamental right to basic educational equality because of being assigned to grossly ineffective teachers, the Court of Appeals said the trial court failed to ask the key question. The trial court should have asked if Group 1 represents a sufficiently identifiable group for purposes of an equal protection action. In the opinion of the appellate court “the unlucky student subset is not an identifiable class of persons sufficient to maintain an equal protection challenge.”

Regarding Group 2, the trial court found that poor and minority students suffered disproportionate harm from being assigned grossly ineffective teachers. Under California law both race and wealth are considered suspect classifications. However, in this case, said the appellate court, the trial court bypassed an initial required question. Did the challenged statutes cause low income and minority students to be “disproportionately assigned to grossly ineffective teachers?”

A statute is facially unconstitutional when the violation flows “inevitably from the statute” and not from the “actions of people implementing it.” In this case, said the appellate court, the challenged statutes by their text “do not inevitably cause poor and minority students to receive an unequally deficient education.” And, “the challenged statutes do not differentiate by any distinguishing characteristic, including race or wealth.”

In the appellate court’s view, trial court evidence firmly demonstrated that staffing decisions, including teacher assignments, are made by administrators, and the process is guided by teacher preference, district policies, and collective bargaining agreements. This evidence, said the Court, is consistent with the process set forth in the California Education Code. Also, the trial court evidence shows that the challenged statutes do not in any way instruct administrators regarding which teachers to assign to which schools.

Regarding expert witness testimony, the Court makes it clear that it is not required to defer to expert opinion regarding the ultimate issue in this case, particularly when the issue “is a mixed question of law and fact.” In any event, “these opinions do not sustain plaintiffs’ burden.”

In sum, said the appellate court, while evidence presented at trial likely demonstrates drawbacks to the current tenure, dismissal, and layoff statutes, “it did not demonstrate a facial constitutional violation.” While the evidence also revealed deplorable staffing decisions being made by some local administrators that have a deleterious impact on poor and minority students in California public schools…[p]laintiffs elected not to target local administrative decisions and instead opted to challenge the statutes themselves. This was a heavy burden and one plaintiffs did not carry.

Appellate Court Decision

The trial court decision is not affirmed. The judgement of the trial court is reversed and the matter is remanded with directions to enter judgment in favor of defendants on all causes of action.

Recently, the California Supreme Court denied review in the case.

Policy Implications

As stated at the beginning of this commentary, public school teacher tenure continues as a controversial subject. While defenders of tenure emphasize its importance as a major protection for teachers (job security), those who call for revoking tenure statutes claim that tenure is a barrier to the flexibility of administrators to assign and reassign senior staff to grade levels and schools where effective classroom teachers are needed. They also claim that tenure statutes (especially the procedural mandates) make it impossible for school districts to dismiss incompetent and ineffective teachers.

While Vergara (2016) is but one case from one state jurisdiction, it is nonetheless instructive. What is of particular importance to local school system policy-makers is the California Court of Appeals detailed review of the trial court evidence—especially its discussion of expert witness testimony. In addition to emphasizing the need to implement the mandates of state tenure statutes in local school system policy and procedure, the appellate court focused on specific aspects of the tenure process and these are:

- the length and critical nature of a probationary period leading up to a tenure decision;

- the importance of evaluation, assessment, and measurement of teacher job performance;

- the early identification of deficiencies in teacher job performance;

- the communication of those identified deficiencies to the individual teacher involved;

- the establishment of a specified period of time for possible remediation of identified deficiencies,

- the possible relationship and impact of a host of outside out-of-school factors (e.g., child poverty) on student classroom learning and achievement;

- the inclusion and use of student test scores as a major criterion in assessing teacher effectiveness;

- the key role played by school administrators in the assignment of classroom teachers to individual schools;

- the possible assignment of effective teachers from “highly performing schools” to “poorly performing schools;” and

- the inclusion of, and weight given to, seniority as a factor in making teacher assignments and in making reduction-in-force decisions.

|

|