|

| State & Local Education News |

Did Terry McAuliffe just invite a school law suit?

Washington Post

June 6, 2016

Could Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe’s (D) executive order automatically restoring voting and other rights for released felons lead to a landmark education decision?

Jim Crow-era “separate but equal” schools defined Virginia’s education policy until ruled unconstitutional by the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision. A unanimous Supreme Court said “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

In light of Brown, Virginia incorporated a promise of a high-quality education for all in Article VIII, Section 1 of the revised 1971 Virginia Constitution.

However, as University of Virginia Law Professor A.E. Dick Howard — who helped write the new Constitution — has explained, the drafters made clear they intended this goal to be “aspirational” only. An “aspirational” goal, unlike a right, isn’t enforceable in court should the state shirk its constitutional duty.

Howard knew the drafters’ intent could be key should education advocates bring a lawsuit. Virginia’s politicians applauded their own cleverness, taking campaign credit for promising equality while constitutionally shielding themselves from legal accountability.

Virginia celebrates summer meals program to provide students with healthy foods

NBC 10 (WSLS)

June 7, 2016

On Tuesday, Virginia First Lady Dorothy McAuliffe, U.S. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack and U.S. Education Secretary John King joined students and other stakeholders at Robert E. Lee Elementary School in Petersburg to celebrate the start of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) summer meals programs.

The two secretaries were joined by U.S. Rep. Bobby Scott and Virginia Secretary of Education Anne Holton to raise awareness of the importance and availability of summer meals for children and teens.

“In Virginia, about 87 percent of students who rely on free or reduced price school meals miss out on summer meal programs each day,” said First Lady Dorothy McAuliffe. “We can and must do more to increase participation in these programs and connect more kids with the healthy food they need to be successful.”

The Hope Center in Roanoke is one of many programs that participate in the U.S.D.A summer meals program. The program provides nutritious free meals for children and teens 18 and younger. Click here to find a site near you.

According to data from the USDA, across the nation, approximately 22.1 million students receive free and reduced-price meals through the National School Lunch Program. But only about one in six of those (approximately 3.8 million) participate in the summer meals programs. That is the critical gap that the summer meals programs work to fill. In 2015, there were more than 66,000 meal sites serving over 190 million meals.

[Opinion] Koch: Cost increases at Virginia public colleges

Richmond Times Dispatch

June 6, 2016

The give and take between members of the General Assembly and the College of William & Mary over the school’s tuition increase once again has pushed the issue of higher education costs to the fore in Virginia. The stakes are large. In 2006, 412,336 students attended the commonwealth’s public colleges. By 2015, that number had climbed to 534,280, a 30 percent increase.

Higher education is big business. In 2015, 56,777 individuals were on public college payrolls in Virginia, and the doctoral institutions’ budgets for 2016-2017 ranged from William & Mary’s approximately $450 million to the more than $1.4 billion of the University of Virginia.

But for what purpose? Are the institutions being operated with the best interests of the citizens of the commonwealth in mind, or instead to satisfy the interests of faculty and administrators at the institutions?

Virginia's high-poverty school divisions get less funding than those of other states, report says

Richmond Times Dispatch

June 2, 2016

Virginia trails the majority of states in the amount of funding dedicated to students from low-income families, according to a report released Thursday.

The research shows that Virginia provides low-income students with 14 to 19 percent more than other students, which is about half the 29 percent other states give on average.

The report, “Weighing Support for Virginia’s Students,” was put together by the Commonwealth Institute for Fiscal Analysis, an economic think tank in Richmond.

|

National & Federal Education News

|

Diversifying the Presidency

Inside Higher Ed

June 3, 2016

The California State University System has named women to lead campuses in five straight presidential searches in 2016, nearly doubling the number of women presidents at the 23-campus system in what some hope signals an accelerating trend toward diverse higher education leadership.

The latest hiring for the 475,000-student university system came May 25, when it named Ellen N. Junn the next president of California State University at Stanislaus. Junn is currently at Cal State Dominguez Hills, where she is provost and vice president for academic affairs. She will take over at Stanislaus State after President Joseph F. Sheley retires at the end of June.

Junn’s appointment comes after Cal State named four other women to presidential roles starting in January, three of whom will be replacing retiring male presidents. It also means the Cal State system will have women presidents at 11 of its 23 campuses. That’s a significant difference from the end of the 2014-15 academic year, when just six of its presidents were women.

Also of note is that Cal State will go into the next academic year with four Asian-American presidents, up from two last year. The change comes at a time when many Asian-Americans have worried they're underrepresented in administrative ranks despite broad success in higher education. The Cal State system also has five Latino and three African-American presidents.

More broadly, the hiring string is a high-profile development for one of the country’s largest higher education systems at a time when women’s leadership at colleges and universities has remained strikingly -- and to many observers disturbingly -- low. In 2011, 27 percent of college and university presidencies were held by women, according to the American Council on Education. That’s sharply out of step with student body compositions at large. The portion of women enrolled at postsecondary institutions has hovered around 57 percent for nearly 20 years, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

University of Missouri campus in Columbia hires black faculty at a slow pace

Kansas City Star

June 4, 2016

In the last two academic years, the University of Missouri campus in Columbia has hired 451 faculty members.

But on a campus that has been torn by protests over a lack of diversity and an oppressive racial climate, just 19 were African-American.

Data obtained by The Star through a Freedom of Information Act request show that in the last two years the Columbia campus hired more than 13 times as many white professors as African-Americans.

|

|

|

Are schools with large percentages of low-income students getting the resources they need?

Two news items caught our eye this past week and provide an interesting window into the challenges faced by school districts with high concentrations of low-income students that are working hard to increase student achievement.

First, a

recent report by the Commonwealth Institute for Fiscal Analysis on how much the state supports school districts with higher poverty rates compared to those with lower rate, received coverage in the

Richmond Times-Dispatch and the

Fredericksburg Free Lance-Star. The report notes the following main takeaway:

In Virginia, the state provides about 14 to 19 percent more for each low-income student than for other students. That’s not as impressive as it might sound. Virginia’s support for low-income students is lower than the 29 percent boost provided on average by states with this support and is well behind some states that spend almost twice as much for each low-income student. Research shows it can cost two to two-and-a-half times as much to help low-income students reach similar levels of performance as students from wealthier families.

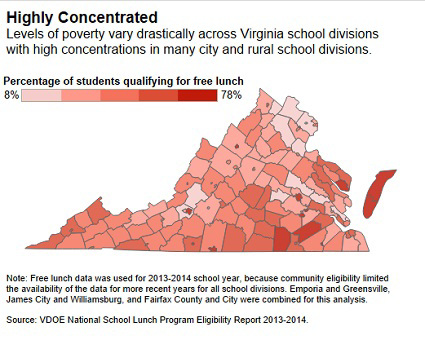

The report points to one of the significant challenges for educators as the

U.S. economy increasingly hollows out the middle class (those with incomes from 2/3 to two times the median household income) - an increasing number of students in public schools come from poor households and those students often face challenges that higher income students don't experience. The report included the map below, showing that some districts face much higher concentrations of poverty in their schools than others. (Click on the map or

here to access the interactive version produced by CIFA.)

|

| Graphic by Chris Duncombe of the Commonwealth Institute for Fiscal Analysis |

The report also notes that significant cuts to state-level education funding during the recent Great Recession hit higher poverty areas harder than lower poverty localities. The recommendation of the report is to increase the top end range of the sliding scale used for the At Risk Add-On funding from 13% to 25% per student in additional funds. Without getting into the pros and cons of the recommendation, we wanted to share it as an interesting policy discussion about the role state-level officials play in deciding how much in additional funds is dedicated to schools with high concentrations of students from low-income households.

The

second article in the Atlantic Monthly that caught our attention looks at how federal level changes in the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) may interact with the way local school systems budget between higher and lower poverty concentration schools within their own district. The writer, Nora Gordon, a professor at Georgetown University, notes that one of the less noticed rules within ESSA is one that requires schools to spend as much in high-poverty schools (Title I schools) as it does in low poverty schools and to calculate this equality in dollar terms, rather than in terms of instructional positions per student. She notes that

existing research shows school systems often end up spending more on "richer" schools because such schools have lower turnover and teacher pay is largely driven by seniority. The rule seeks to force school systems to pay attention to this, but may also force schools to move teachers from one school to another to comply with the rule. Doing so, sometimes on short notice and potentially against the teacher's personal preference would potentially result in significant dislocation and controversy as parents who like a reassigned teacher complain to school officials. Gordon highlights that

districts might respond to these pressures by continuing to concentrate poor students in Title I schools rather than trying to break up concentrated poverty. This is because compliance with the rule is easier if students are clustered in a few Title I schools. Similarly, they could abandon economic-integration efforts that dilute high concentrations of poverty, such as magnet schools, redrawing boundaries, or increasing parental-enrollment options beyond neighborhood boundaries.

In either of these instances, possible solutions can be debated, and the range of possible solutions is constrained by several broad parameters in deciding whether and how to change funding formulas, including legal and fiscal constraints. In concluding our brief look into these complex issues, we wanted to share two CEPI resources that may provide some sense of how rigid constraints are.

First, regarding the legal constraints, this week we reach back a few years to share some

excerpts from Dr. Vacca's 2006 Education Law newsletter that looked at legal parameters for equity in education funding.

With regards to fiscal constraints, one of the key questions all education officials face is whether the taxpayers would be willing to contribute more of their earned income for increased funding for public schools. So we also are happy to share insights in our

Poll Snapshot below on how willing the general public in Virginia is to pay more in taxes so that more funding can be channeled to low-performing schools in high-poverty areas.

We hope you have a great week!

Sincerely,

CEPI

|

CEPI Poll Snapshot - Pay Extra to Support Low-performing Schools?

A short data insight from our

Commonwealth Education Poll.

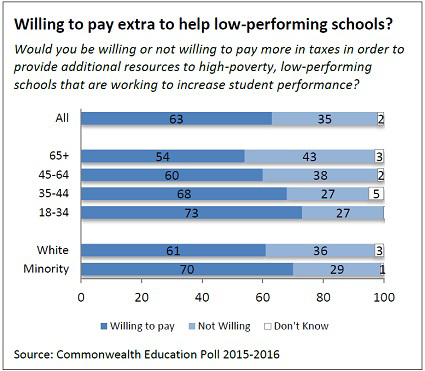

Repeated studies have shown that there are unique challenges to providing high quality education in high-poverty environments. Given that a majority of respondents see SOLs as providing equal standards and accountability to school systems across different types of communities, an interesting follow-up question is whether the public is willing to pay more in taxes in order to provide additional resources to high-poverty, low-performing schools that are working to increase student performance. A majority (63%) of respondents would be willing to pay more in taxes to do so.

There was significant variability, however, between different demographic groups.

|

|

Younger respondents were more likely to support additional resources for high-poverty, low-performing schools. Among 18-34 year-olds, almost three-quarters (73%) were willing to pay more in taxes, while that proportion dropped to 68% among 35-44 year-olds, 60% among 45-64 year-olds and 54% among those 65 or older. Likewise, minority respondents (70%) and Democrats (76%) were more likely than whites (61%) and Independents (57%) and Republicans (51%) to be willing to pay more in taxes to increase resources flowing to high-poverty, low-performing schools.

(To read the full poll, visit our

website.)

|

|

Public School Finance: The Cost of Basic Education

Excerpted from

Dr. Vacca's April 2006 Education Law Newsletter.

Overview

The purpose of this year’s April commentary is threefold. First, the commentary will briefly restate the law involving public school finance. Second, recent case law on point will be presented in an effort to up-date the school finance scene over the past twelve months--- as the courts have continued on their quest to establish adequacy in funding. Third, the last section will suggest legal and policy implications facing local public school officials in 2006.

Historical Antecedents

Over the past forty years school finance has remained a constant source of litigation in this nation’s courts. As Alexander and Alexander observed, “Although the volume of cases is relatively small compared to other fiscal matters, the issue of the constitutional rights of students and the resulting impact on state school finance has probably been the most widely publicized area of school finance.” Alexander and Alexander (2005)

Beginning with such early cases as McInnis v Shapiro (N.D. Ill. 1968) and Serrano v Priest (Cal. 1971), and reaching a high point in the United States Supreme Court’s landmark decision in San Antonio v Rodriguez (1973), judges struggled with issues raised by plaintiffs who claimed that a direct connection existed between levels of state funding available to local school systems and resulting disparities in student academic performance and achievement.

The early cases focused on the fact that state school funding formulas heavily relied on local real property taxes. In essence plaintiffs claimed that a reliance on the value of local property created an inherent discrimination against children who happened to be born in communities with low real property values. Plaintiffs claimed that the quality of educational opportunities available to children of school age was determined by the wealth of their parents and neighbors. Vacca and Bosher (2003) To put it another way, the emphasis in early case law was on connecting the differences in the amounts of state funds made available to local school districts (input), the disparities in local spending per student, and levels of student academic progress and productivity (output). The claim was that increased funding promoted increased spending (per student in average daily attendance), and increased spending produced increased educational quality.

The Impact of Rodriguez. The United States Supreme Court’s decision in San Antonio I.S.D. v Rodriguez (1973) initiated a new era in public school finance litigation. As Justice Powell stated: (1) the importance of education does not in and of itself bring school finance issues under the Equal Protection Clause, (2) wealth discrimination alone does not trigger a strict scrutiny analysis, and (3) solutions to public school finance problems where they exist must come from state legislative bodies. Thus, a new wave of finance litigation was spawned as the locus of litigating school finance issues and efforts to bring about finance reform moved to the states.

Decisions from state appellate courts, in the months following Rodriguez, revealed a new trend in school finance litigation. Such cases as Robinson v Cahill (N.J. 1973), Milliken v Green (Mich. 1973), Horton v Meskill (Conn. 1977), Hernandez v Houston, I.S.D. (Tex. 1977), Pauley v Kelly (W.Va. 1979), and others are examples of the new breed of school finance case. At one time more than twenty states had public school finance cases before their highest court. Vacca and Bosher (2003)

Public School Finance in the 1980s and 1990s. Experts in public education tell us that “the twin themes of efficiency and measurement characterized the approach of the schools during the second half of the 20th century just as they did during the first half.” Short and Greer (2002) These authors stress that the objectives remained the same; namely, “guaranteed results in student achievement and efficient use of resources.”

As public school finance litigation and subsequent legislative reform efforts moved through the 1980s and into the 1990s, a shift occurred in judicial philosophy and a new judicial standard of analysis emerged. When deciding a public school finance dispute judges consistently focus on the constitution of the state involved and ask the following questions:

- What is the meaning of the language contained in the education clause of the state’s constitution? A good example can be found in the Constitution of Virginia where it says, in part, that the General Assembly shall “seek to ensure that an educational program of high quality is established and continually maintained.” VA. Constitution, Article 8, Section 1 (July 1, 1971)

- Based on that interpretation, what is that state’s constitutional duty to fiscally support education for all school-age children in that state?

- Is that state meeting its constitutional obligation? Dayton (1992)

State court judges became less inclined to focus on disparities in funding and inequities in student expenditures (input), and more inclined to search for fiscal formulas that achieved adequacy in educational opportunities made available to all students of school age, as demonstrated by increased student academic progress and achievement (output). The roots of the shift can be observed in such cases as Rose v Council for Better Education, Inc. (Ky. 1989), Edgewood I.S.D.v Kirby (Tex. 1989), Tennessee Small School Systems v Mc Wherter (Tenn. 1993), Abbott v Burke (N.J. 1994), Scott v Commonwealth (Va. 1994), and De Rolph v State (OH. 1997).

Read the full analysis and other Education Law Newsletters on

our website. |

|