|

Recent State and Local Education News

|

State Council of Higher Education for Virginia's budget request adds policy to numbers

Richmond Times-Dispatch

October 31, 2017

The State Council of Higher Education for Virginia has tried to sweeten its $352.4 million budget request with policy plums for legislators who are looking for ways to reduce the cost of higher education for students and taxpayers.

SCHEV unanimously adopted its request on Tuesday for $241.1 million in state funds and $111.3 million in the next two-year budget, and included more than half a dozen proposed policy changes, including a hotly debated proposal to lower the cap on annual fee increases for noneducational initiatives such as athletics from 5 to 3 percent.

The budget request, reduced by nearly $14 million from the original staff recommendation, also suggests that colleges and universities be allowed to keep unspent state money in institutional reserve funds, give them more freedom to increase admissions of out-of-state students to lower state costs, and return to a stable two-year budget cycle instead of yearly swings in revenues.

Virginia-based Strayer to acquire Capella Education in $1.9B deal

Associated Press

October 30, 2017

Strayer Education is tying up with Capella Education in a deal worth about $1.9 billion as the U.S. Education Department considers rolling back Obama-era rules that would have erased federal loans for students defrauded by for-profit colleges.

The two schools stood out from others mired in inquiries about students left with large debts and limited prospects. Strayer University and Capella University will continue to run as independent institutions with separate boards.

Strayer and Capella together serve about 80,000 students across all 50 states. Both universities will operate under Strayer Education Inc., with corporate headquarters in Herndon. Strayer Education will be renamed Strategic Education Inc. and still use the ticker symbol “STRA.”

Report: Virginia's high-poverty schools don't have same opportunities for students

Richmond Times Dispatch

October 30, 2017

There are “striking deficiencies” in educational opportunities for students in high-poverty Virginia schools, a new report has found.

Students in high-poverty schools, or schools where at least 75 percent receive free and reduced-price lunch, have less access to core subjects like math and science, lower levels of state and local funding for instructors, who are less experienced in these schools, according to a report from The Commonwealth Institute for Fiscal Analysis, a research organization based in Richmond that focuses on economics and policy.

“All students are not being given the same opportunities to pursue their dreams upon graduation,” said Chris Duncombe, a senior policy analyst at The Commonwealth Institute and author of the report, which was released late last week.

Future of public education in Virginia at stake in governor’s

Washington Post

October 5, 2017

The outcome of Virginia’s race for governor, the country’s marquee statewide election this year, will have widespread significance for the state’s roughly 1.29 million schoolchildren, political observers and education experts say.

“The governor’s race matters a whole lot for what public education will look like in Virginia in the days ahead,” said Sally Hudson, an assistant professor of public policy, education and economics at the University of Virginia. |

Recent National Education News

|

Education Department to Withdraw 600 'Out-of-Date' Guidance Documents

US News and World Report

October 27, 2017

The Department of Education announced Friday it is in the process of withdrawing nearly 600 pieces of guidance – regulations federals officials say are “out of date” but which some advocates say are an attempt to rollback protections for minorities and disabled students.

“Each item has been either superseded by current law or is no longer in effect,” Education Department officials wrote in a press release. “Removing these out-of-date materials will make it easier for schools, educators, parents and the public to understand what guidance is still in effect.”

In April, President Donald Trump signed an executive order directing the agency to identify areas where the federal government has exceeded its authority and overtaken states’ and local school districts’ ability to make decisions for themselves about things like standards, testing and teacher evaluations.

Specifically, the executive order gave Education Secretary Betsy DeVos 300 days to conduct a study to “determine where the Federal Government has unlawfully overstepped state and local control.” That directive has resulted in a series of controversial regulatory pauses, including in matters regarding Title IX and sexual assault on campus, as well as higher education regulations aimed at curbing bad actors in the for-profit college sector.

The holistic review has also turned up hundreds of pieces of guidance that are out of date and no longer play a role in the federal education policies that states and school districts follow, according to department officials. That includes, for example, directives for how states should implement parts of old iterations of education laws, like the George W. Bush-era No Child Left Behind, pointers for how states should spend money that specifically relate to previous fiscal year appropriations and records of historical occurrences, such as a 1997 flooding that overwhelmed North Dakota, South Dakota and Minnesota.

The announcement comes as the department has received a wave of pushback from Democrats, civil rights groups and special education advocacy organizations after it said it would rescind 72 documents that provide guidance on students with disabilities served under the Rehabilitation Act and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

|

|

|

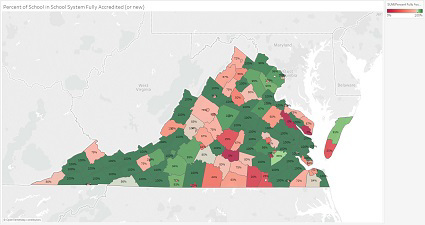

Where are schools that did not receive full accreditation in 2017?

For school systems, aside from an event that physically harms students or faculty, the scariest news possible is that one or more of your schools are not fully accredited. Back in September, the annual release by the Virginia Department of Education (VDOE) of accreditation results for schools across the Commonwealth held good news. As the

press release from VDOE noted, 86% of schools were fully accredited this year, up from 81% last year and 78% the year prior.

Regular readers of Compass Point may remember our visual analysis of the results from 2015 and 2016 and so again this year we wanted to look at several aspects including:

- which school systems had all their schools fully accredited?

- where are schools that did not receive full accreditation (meaning they were warned or denied)?

- are those schools highly concentrated in certain school systems or evenly spread out?

- and for those receiving the harshest category (denied) where are they concentrated.

The set of three visuals can be accessed

via this link or by clicking on any of the graphics below.

First we look at the percentage of schools in each school system that were fully accredited (or so new that they do not yet have enough of a track record to be rated for accreditation). As the VDOE noted, 65 school systems had 100% of their individual schools receive full accreditation, up from 53 last year and 36 the year before year. (Certainly worth celebrating.) Of course in the map below, those are the dark green school systems. Those in lighter shades of green did not have 100% of schools fully accredited but were above the state average of 86%. Those in shades of red fell below that 86% average state mark.

|

|

The take aways from this map are that school systems with at least one school receiving a warning or denial are spread across the state, though in general, a lot of western Virginia counties and non-urban central Virginia counties had 100% full accreditation rates. School systems with very low rates are generally concentrated in South Central Virginia, in larger urban areas and along the Chesapeake Bay.

Next we take a look at where the largest numbers of warned or denied schools are located. Keep in mind that in a small 3 school district (one elementary, one middle and one high school), having just one school receive a warning would result in a system-wide rate below the state-wide average of 86%. As can be seen below, a fairly large number of schools that were warned or denied accreditation fall in the larger urban areas.

The third graphic makes this even more clear. As was the case last year, close to 30% (73 of 243) of all schools that were warned, denied or fall in the "to be determined" category are in four school systems - Richmond City, Norfolk, Henrico and Newport News.

Not surprisingly, these systems are also among those with high overall poverty rates and also which have large or growing numbers of non-white students. A

recent report from the Commonwealth Institute for Fiscal Analysis points to some of these correlations between concentrated poverty and race in identifying systemic issues that confront those relatively few schools that repeatedly fail to reach accreditation.

We mention this because, in any debate about the success of schools, whether funding is similar across the board or targeted to school systems that require the greatest growth to meet key benchmarks is a key policy question. In

this week's poll snapshot we look back at last year's poll where we asked the public whether they would be willing to pay more in taxes to increase the funds available for public schools and also whether they would do the same to increase funds specifically for high-poverty, low-performing schools.

We hope you find this collection of analysis and insights useful.

Sincerely,

CEPI

|

Poll Snapshot - Support for increased funding - does targeting high-poverty schools increase support?

In our past Commonwealth Education Polls we've asked two questions about whether respondents in our representative sample of Virginians would be willing to pay more in taxes in order to have funding increased for schools in general, and for low-performing schools in high-poverty areas specifically. Until recently, this question was likely to be applicable in folk's minds to urban high poverty schools, but with increased attention to the challenges faced by rural districts facing the decline of traditional industries, the responses may be relevant to those areas as well.

First, the question of whether the public is willing to pay more in taxes to increase funding for schools is a key baseline. The portion of the population willing to see their own taxes increased for schools in general hovers between 53 and 60 percent over the past 5 years, with a potential slight drop (the gap is just inside the 95% confidence interval for the poll). But certainly those in areas with larger numbers of schools that lack accreditation (Tidewater and South Central) a greater percentage are willing to see taxes go up for this purpose. Still, there's only a small majority in any region. Interestingly, there is no statistical difference on this question between white and minority respondents.

In contrast, two-thirds (67%) of respondents would be willing to pay more in taxes to provide more resources specifically to high-poverty, low-performing schools, with regional breakouts ranging from 57% willing in the Northwest region to 71% willing in the Tidewater area. Democratic respondents are significantly more likely to be willing to pay more in taxes for this purpose, but unlike the general school spending question above, so are minority respondents. Younger Virginians are also more likely to be willing to pay more.

So targeted use of additional education dollars is likely to be more popular with the public than an accross the board increase in funds available for education.

To read the full 2016-17 poll, visit our

website.

|

|